Conversing with the Dead

Letters discarded, letters found, and the space of the missing conversation

In the Athens block of flats where I grew up, the arrival of the postman was an event. I can still see Kyrios Yorgos in his navy-blue uniform and his well-worn, deformed leather satchel, overflowing with letters, slung across his body. His face was flushed and his nose even more so. A whoosh of energy enveloped him as he appeared at the entrance frame, spreading much-needed cheer in our household.

His appearance meant one of two things: money and letters. On the last working day of every month, he brought Yaya’s - my grandmother’s - pension in cash. While he counted the paper money in Yaya’s presence, Mama poured out a shot of brandy or whisky for his trouble. He knocked it back in one go, and was on his way, taking the cloud of cheer with him again.

But the arrival of letters was the highlight of the day: unexpected, although always anticipated from different sources. Baba and Uncle Yorgos, one of Mama’s brothers, criss-crossed the oceans as officers of the Greek merchant navy. Baba didn’t write often, to me at least. Now and then, he sent me a letter; strictly speaking it was not a letter, more an envelope containing a brief note and a ten- or a twenty-dollar bill wrapped in carbon paper to avoid detection. When I was very small, I loved individually wrapped moist tissues, and he sent me one of those in each envelope. They had Japanese characters printed in turquoise all over the wrapping. In a little free space in the corner, he squeezed, To my Sofia, with kisses, from Baba. I hoarded those in an old handbag of my mother’s, thinking – expecting? - that they would keep for ever. When I opened one once, I found it had dried out.

Other sources of letters were Uncle Manos, Mama’s younger brother, and his wife Nina who lived in London. Manos, a naval engineer, travelled often, but they both wrote often with their news, talking about the magical place that was London for me then. Mama’s and Yaya’s Lebanese Christian ex-neighbours from Egypt, also wrote to them in French with news about sons’ weddings, daughters’ new babies, deaths, news from the city of Alexandria they had lost.

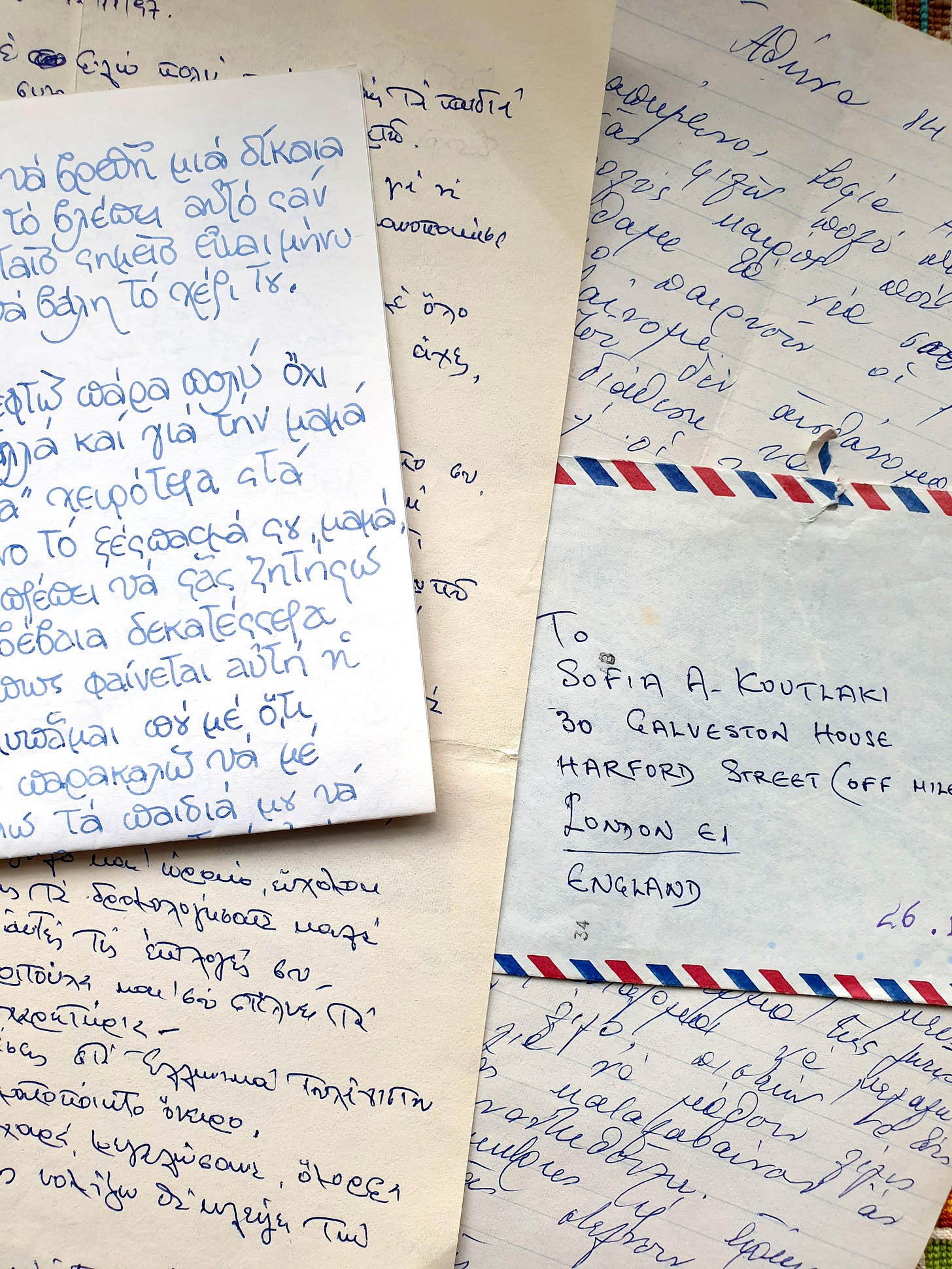

None of the family letters has survived. During the clearance of the Athens flat, I found hundreds of photos and lots of postcards and greetings cards. Only a few letters dating back to the Egypt time escaped binning; the rest of it is gone. Baba, I was told, threw Mama’s letter into the sea and Mama, in a pique, also got rid of all Baba’s letters, written between their engagement in 1959 and his retirement in 1981. Uncle Yorgos’ letters between the mid-60s when he joined the merchant navy and the mid-80s when he took early retirement, are also gone, presumably thrown away as soon as they were answered. Manos’ and Nina’s letters to the family in Athens are also missing, except one dated early 1986, a couple of months before Manos’ premature death at 48.

I grew up to become an avid letter writer. I started as a teenager, writing to a friend away in military service, and went on to write for years to another friend in my native island of Kassos and then to New York where he emigrated. Then came the language project and the exchange of letters with pen-friends, with the one pen-friend, The Tall Dark Stranger, standing out among them - and still standing. Hereby hang many more tales.

I wrote a lot of letters to my parents, Yaya, Eleni and my Athens university friends between 1987 when I came to London and the early noughties, when telephone communication became less expensive and we all stopped writing letters altogether.

My side of the conversation is missing from the Athens archive: only two letters of mine were found in Athens. But I kept my side of the bargain: before I left for Iran in 1997, I wrapped my parents’, Yaya’s, my sister Eleni’s, and my friends’ letters in plastic sheets, sealed them with cargo tape, stored them in our humid garage in west London, and forgot about them, only to rediscover them intact while clearing out the garage recently. The letters between me and The Tall Dark Stranger went back and forth between London and Tehran twice, but have never been re-read to date.

As a life writer, I see these letters as snapshots of life moments but also as a treasury of words that may never have been spoken. The act of preserving the letters of those dead or aged salvages a moment, insights into their character, their voices beyond the limits of their life. As I re-read Baba’s letters I hear his aspirations for me, his disappointment with my life choices, his encouragement to strive for a better job, and his repeated reassurances that he would always be there for me no matter how much I hurt him. Mama’s letters often share social news (“gossip”, Baba calls it) like engagements, weddings, illness, death, everyday complaints of pain, expressions of missing me and the children, requests that I speak to the children in Greek, so that they can speak with them when we meet again. They often express hopes for the future, for meeting up again, for difficulties to be over, for good times to be had in an indeterminate future.

I wonder where Kyrios Yorgos, the jolly postman of my childhood, got his energy and good spirits from. My rational side says that he was tipsy from the number of drinks he must have been treated to throughout the day, but my poetic side tends to think that the good cheer he spread delivering letters must have brushed off on him. That magical feeling of connection, of touching a piece of paper that a loved one has touched, contemplating that someone far away has sat down with themselves, opened up a letter pad and the space to meet up with you, unfolding themselves in the flow of ink, moment to moment in time.

What do the letters reveal and what do they cover up? This is my life writing project: to meet the dead and converse with them, to supply the missing side decades later. My part of the conversation then was silenced, but I can have a new conversation in the ever-unfolding now that I am granted by the universe.

The rest of the strands…

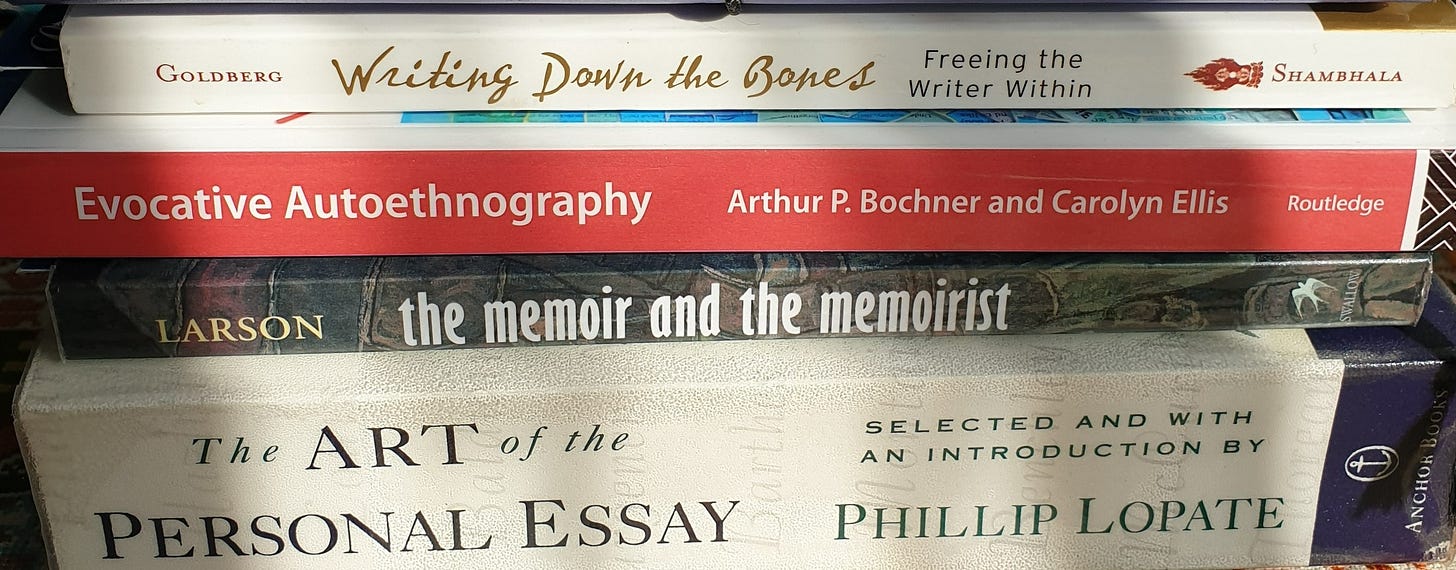

Memoir and Life Writing

The Memoir and Life Writing group at The London Writers Salon, continues to meet up on the 1st and 3rd Thursday of each month, to get to know each other, talk about our work and share experiences and resources.

The next community meeting of the Memoir and Life Writing group is on Thursday 16 March, 5-6 pm GMT, when we will share ideas about memoir structure.

If you would like join hundreds of other writers writing in community, join the free Writers’ Hour; one of the four daily sessions is bound to fit in with your daily schedule. We can’t wait to welcome you and to write together!

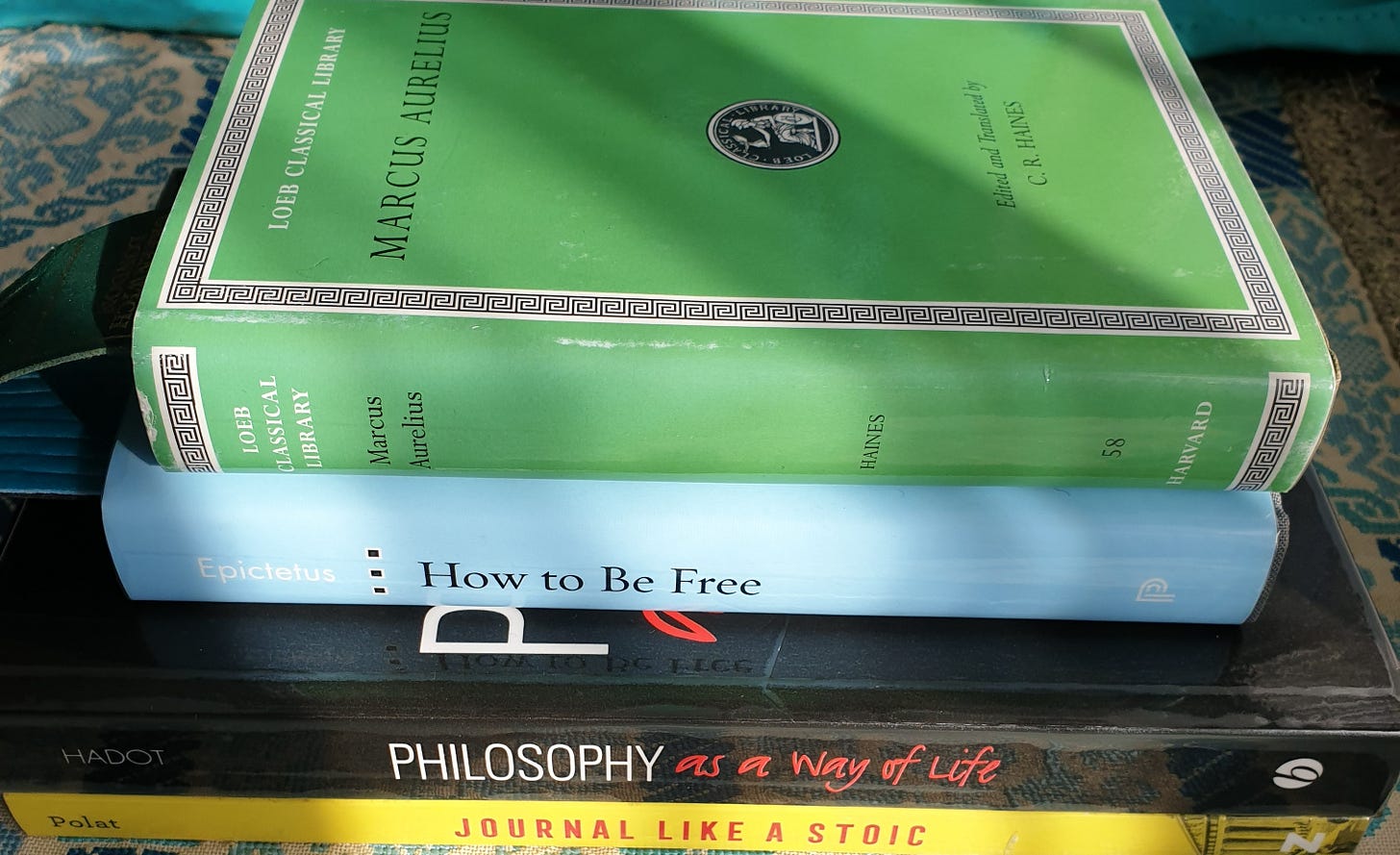

The Stoic Salon

The Stoic Salon plans more inspiring events in the near future, so make sure you sign up. We always welcome new friends!

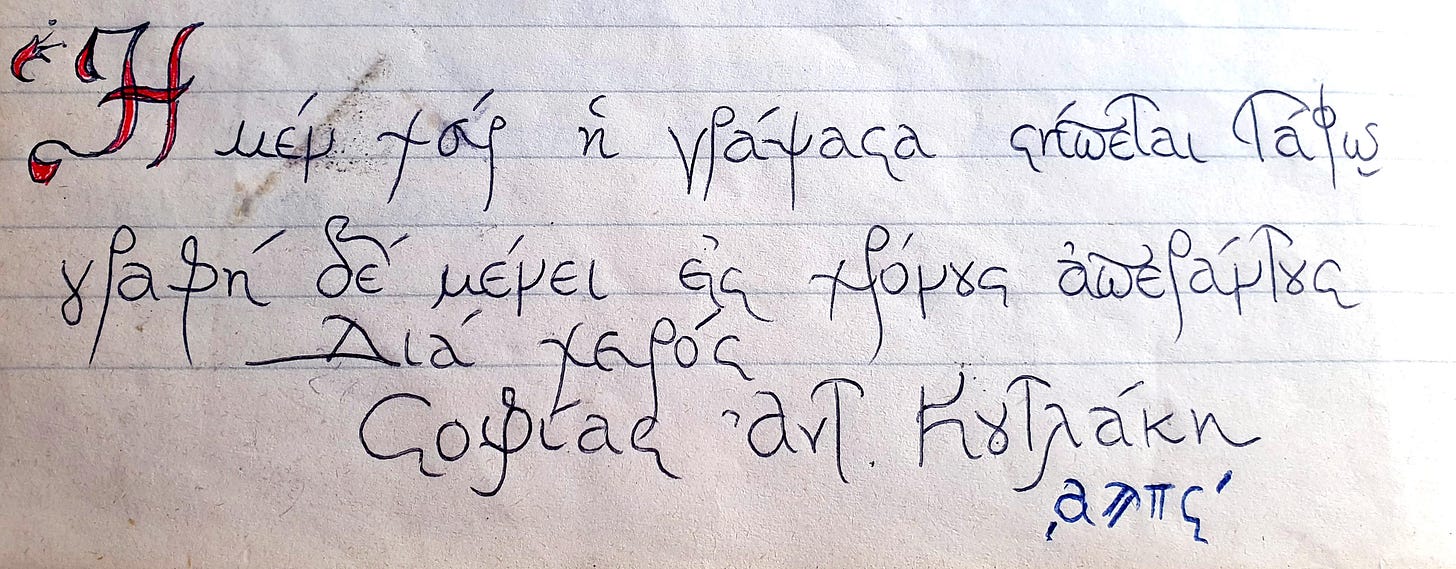

The heart meets the (left) hand in an embrace of imperfection

The hand that wrote out [this manuscript] is now rotting in the grave

but the writing remains for the eternity of time.

By the hand of Sofia A Koutlaki, 1986

This faux-Byzantine inscription was found on the last page of my old French workbook: it was meant to reproduce an inscription from old manuscripts, painstakingly copied in ancient monasteries. The idea of the written word surviving death inspires my 22-year-old self to sign off with the formula encountered in Palaeography class, where I spent a long time trying to decipher sometimes illegible handwriting. I have now come full circle as I read family letters.

Hello Viktoria and thank you for reading and engaging. I always miss the exquisite joy of receiving a letter! What a precious opportunity you have to exchange letters with your mother-in-law: I'm sur he appreciates them a lot.

A lovely reflection on letters, a few months ago my cousin sent me a package of old postcards sent by my parents to my grandparents. You are right, you can hear the undertones of their words, the messages not written, or is that just me seeing the unseen stories from knowledge gained after their deaths. xxx