The obstacles and the ways

Stoic thought and practice in a life with chronic health conditions

What do you do when you come across obstacles, practical and emotional?

Do you have a practical go-to toolbox?

These two prompts sparked a helpful discussion at a recent meetup of a local support group for people living with chronic health conditions. Several good ideas popped up: practising mindfulness, self-awareness and breathing techniques; embracing nature, taking care of plants or simply walking in a park; follow your passions; practising creativity, such as painting, doing mosaics, singing, knitting; pacing yourself and understanding and accepting your body’s limitations; simplifying your life.

When my turn came, I mentioned that I’ve found Stoic thought an enormous help, and gave a brief explanation of the Dichotomy of Control. My supportive friends in the group would like to know more - would I be able to give them a short introduction at the next meetup? This presentation took place two days ago: it was a lively, engaging conversation that felt good, as we shared our common experiences. Here follow the written-up notes that I promised I’d share.

There are so many excellent introductions to Stoicism out there (some links follow at the end of the post), that to add one more seems redundant. Over the last three years, I’ve written briefly on Stoicism, mainly as responses to events in my life, but in this instance, I enjoyed the exercise of putting together a basic overview, specifically focused on how Stoic thought and practice is helping me cope with several chronic health conditions.

Any brief account of Stoicism (for example here and here) will always mention Zeno of Kitium, the middle-class merchant hit by adversity and loss of property; Epictetus, the manumitted slave; Seneca, the philosopher and playwright; and Marcus Aurelius, the Roman Emperor, for a time the world’s most powerful man. This list, far from exhaustive, shows how people of various backgrounds and with different life experiences share common ground in their exploration of what makes for a good life. Here follows my personal take on Stoicism at the point I find myself now - it may well develop over time as I continue delving into the texts and the practice.

The aim of my existence is:

to find ‘the good life’, not necessarily in terms of material possessions and social standing;

to achieve excellence of character or ‘virtue’ (the ancient Greek arete), which comprises Courage, Justice, Temperance and Wisdom;

to live sincerely and authentically, according to nature;

to flourish and find contentment, whatever the external conditions of my life may be.

What’s your take on ‘the good life’?

Like everyone else, I have a limited lifetime and limited resources. As is the case with people living with one or more chronic conditions, limited energy, fatigue and pain are also constant life companions: the battery just won’t hold the charge. In my case, energy is sapped by constant arthritic pain and a cirrhotic liver. It therefore makes sense to be realistic about what I can do with the resources I have.

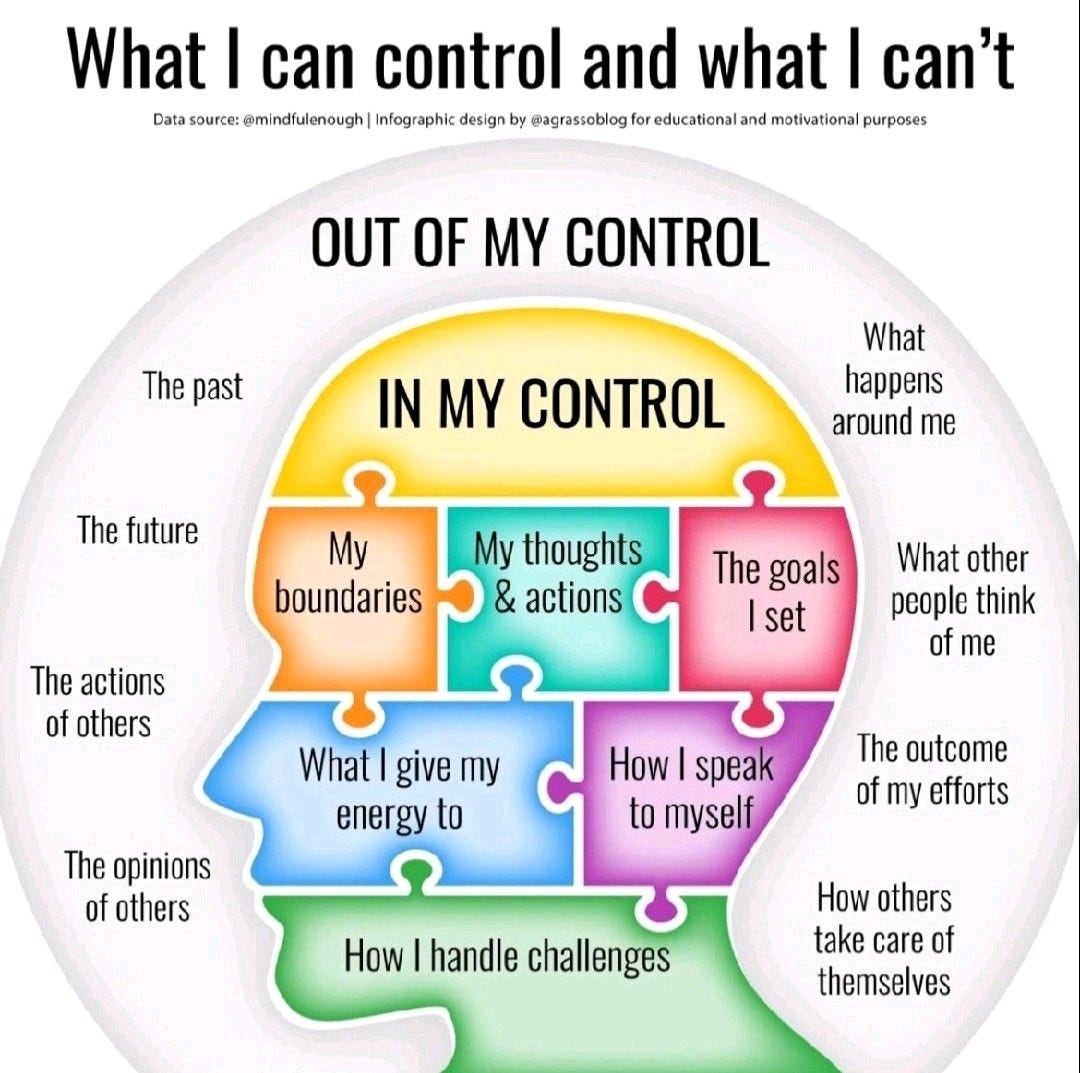

(Data source @mindfulenough infographic design by @agrassoblog)

The image above lists some of the items that fall under my control and those that don’t - in short, it highlights the dichotomy of control. On Friday we went round the group and added more to these, so our final list looked something like that:

What I control

My thoughts, actions and judgments; how I speak to myself; the stories I tell myself; the goals I set for myself; how I handle challenges; what I give time and energy to - in other words, the ability to move towards something (adversion); my boundaries - or the ability to move away from something (aversion).

This piece of advice from my father illustrates this dichotomy. He had crossed the Atlantic and the Pacific many times as a sea-captain in charge of cargo ships. “When a storm rages and the huge waves hit straight at the prow, you need to reduce speed and adjust course so that the waves crash at the vessel from the side. You are still heading for the port of your destination: you may reach it later than recorded in the route plan, but you do everything in your power to reach it safely.”

What I do not control

The past and the future - in any case, when things happened and when things will happen was and will always be the present moment; the actions, opinions and judgments of others; how others take care of themselves; what people think of me; what happens around me: world events, politics, the weather (the storm hitting the ship); the outcome of my efforts.

Have you got anything to add to these two lists?

Non-attachment to outcomes

This last one, the outcome of my efforts, is especially important. When I was diagnosed with liver cirrhosis four years ago, I was told that the condition is not reversible; the best one can aim for is to arrest its progression. The hepatologist ran through the care guidelines: minimise salt in the diet, avoid raw or undercooked food, control blood sugar levels, exercise regularly, lose weight. However, she stressed that even if all guidelines are followed, there is no guarantee that the liver will not turn cancerous or fail. In time, I saw the parallel between the doctor’s words and the parable of The Stoic Archer, who may spend months training for an archery competition, but a sudden gust of wind may cause the arrow to fly off course.

Anger

The diagnosis came as a bolt from the blue, and hard to hear. Anger that I didn’t even know was there boiled over, and hit both the quick and the dead. Swarms of whys clouded my mind and raised unexpected storms that caught those closest to me quite unawares, during lockdown to boot. It took me years to realise that my anger stemmed from resentment with the past behaviour of others, from the desire to control their current behaviour, from lack of acceptance that I could not control these and from lack of awareness of what I could have done about all this myself. (I now find this affirmation useful as an antidote to anger: “others can choose how to act; I have no control over the choices of others, neither do I expect to have.”)

Acceptance

I am still working on all this, trying to get to a state of acceptance which is the only way through to a life of contentment. I can’t take time off from diabetes or arthritic pain but I can try to accept them as if I’d chosen them (Eckhart Tolle’s words, still hard to accept) and learn to see what they bring to my life as a whole. I can’t express it any better, so I stand aside and let Marcus say it better.

So there are two reasons why you should be content with your experience. One is that this has happened to you, was prescribed for you, and is related to you, a thread of destiny spun for you from the first by the most ancient causes. The second is that what comes to each individual is a determining part of the welfare, the perfection, and indeed the very coherence of that which governs the Whole.

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 5:8 (tr. Martin Hammond)

It feels good to wake up full or energy and pain-free, but in my experience now, it does not happen often. If I make my contentment in life contingent upon health, lack of pain and the inexhaustible energy I seemed to have earlier in life, I will trap myself in a cage of my own making. I need to sever this connection, and instead I try to focus on what I control, like following medical advice, listening to my body’s signals, accepting my limitations, being kind to myself and helpful to others.

Silver Linings

At the group session last Friday, I asked whether chronic health challenges had brought a silver lining to anyone’s life. One member said that she gained more leisure time, which was non-existent when she worked full time; another said that although she used to work in a caring profession, she developed deeper empathy towards the sick after she became unwell herself. She also felt compassion towards her now dead father, after making the connection between his constant short-temper and the fact that he had to continue working even though he was sick. As they spoke, I felt as if they were telling my own story.

So it seems that chronic illness can bring about wisdom. Gabor Maté says that his terminal illness patients often said that their illness was the best thing that happened to them. Even as they knew the illness would bring about their death, they recognised that it had led them to becoming whole. His account resonates with my experience: my health problems started over twenty years ago, like alarms that went off at intervals. I kept pressing the snooze button and going back to how I had always carried on. The body kept sounding the alarms more and more frequently, but I just ignored it - after all it had always worked without complaint, so what was its problem now? It was only after the diagnosis of the liver cirrhosis that I paid attention to the alarm. After the initial anger was largely processed, I paradoxically felt grateful for this (latest?) health condition, and came to think of it as a watershed moment.

Journaling practice

A lot of this processing happens in the pages of my journal, as I try to follow Marcus Aurelius’ example. Whenever I sit down to journal, I picture him sitting in his tent at night, scribbling away. He addresses himself with ‘you’, in the space he opens up on the blank page, where he contemplates the transience of the world and works through his fear of death, which he met, incidentally, on a day such as today, 17 March 180 AD. The Meditations, which bears the Greek title Notes to Self, is in effect his personal journal, written mostly while he was on military campaigns hundred of miles away from his native Rome. It was never meant for publication, but it is arguably the most popular of all Stoic texts, possibly because he meets himself in these pages without filter and without thinking how they will be read.

To conclude this personal and, no doubt incomplete account, I must confess that I am still mostly a fair-weather Stoic: when a storm breaks out, I still do everything my father advised me to avoid. But at least I remember his advice, even if after the fact. I keep trying to apply the Stoic teachings and not to be discouraged when I don’t get things right. I also continue to enjoy the journey for as long as it lasts: the effort and the enjoyment lie within my control, even if the outcome doesn’t.

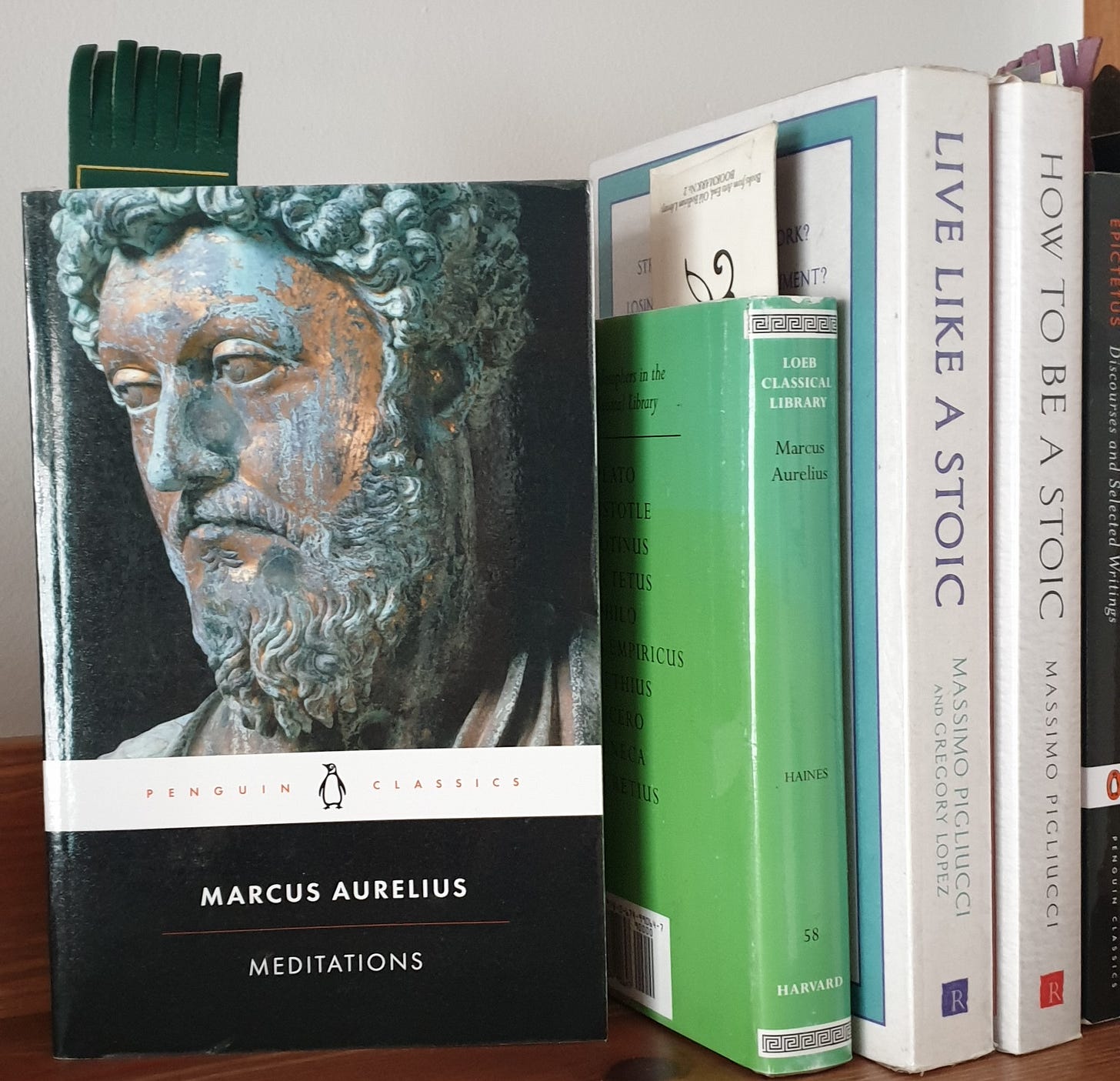

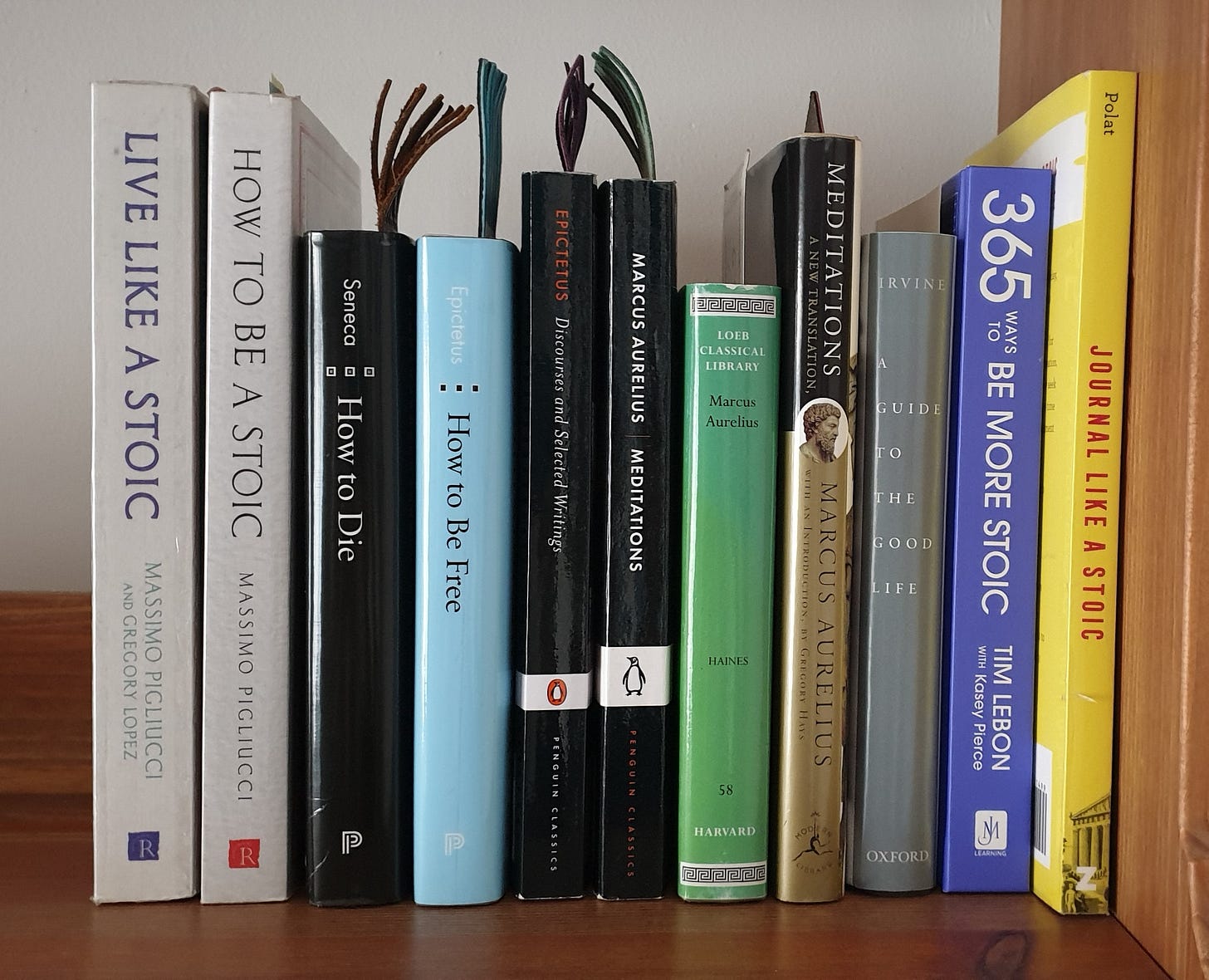

If you would like to explore Stoicism further, here follows a list of books I have read and blogs I follow. Also do share any comments or insights below. Thank you for reading!

A Selective Reading List

The ancient texts

Handbook and Discourses - Epictetus

Letters to Lucilius - Seneca

The Meditations - Marcus Aurelius

Introductions to Stoicism

The Obstacle is the Way - Ryan Holiday

A Guide to the Good Life - William B Irvine

How to Be a Stoic - Massimo Pigliucci

Practical Courses (in book format)

Live Like a Stoic: 52 Exercises for Cultivating a Good Life by Massimo Pigliucci and Gregory Lopez. (In the US the same book is published under the title A Handbook for New Stoics: How to Thrive in a World out of Control). In his newsletter Figs in Winter Massimo has just started an online 52-week practice working through the book. Check it out here. From my own experience, my good friend Kathryn Koromilas and I led an online group working through this book, and I posted my weekly check-outs in previous posts; for example here is the one on anger in Week 47. One month in, the authors visited the group online and answered questions - you can watch the event here.

The Daily Stoic - Ryan Holiday

365 Ways to Be More Stoic - Tim LeBon

Journal Like a Stoic - Brittany Polat

Newsletters

Modern Stoicism and its blog Stoicism Today

What is Stoicism - Allan

Figs in Winter - Massimo Pigliucci

Stoicism for Humans - Brittany Polat

Philosophy as a Way of Life - Donald Robertson

Other books (mentioned in the presentation)

The Power of Now and A New Earth - Eckhart Tolle

When the Body Says No - Gabor Maté (if you live with a chronic and/or serious health condition, I cannot recommend this book enough!)

Cured - Dr Jeff Rediger (so inspiring - I plan to write about this book in a future post)

Got more suggestions? Share them in a comment!

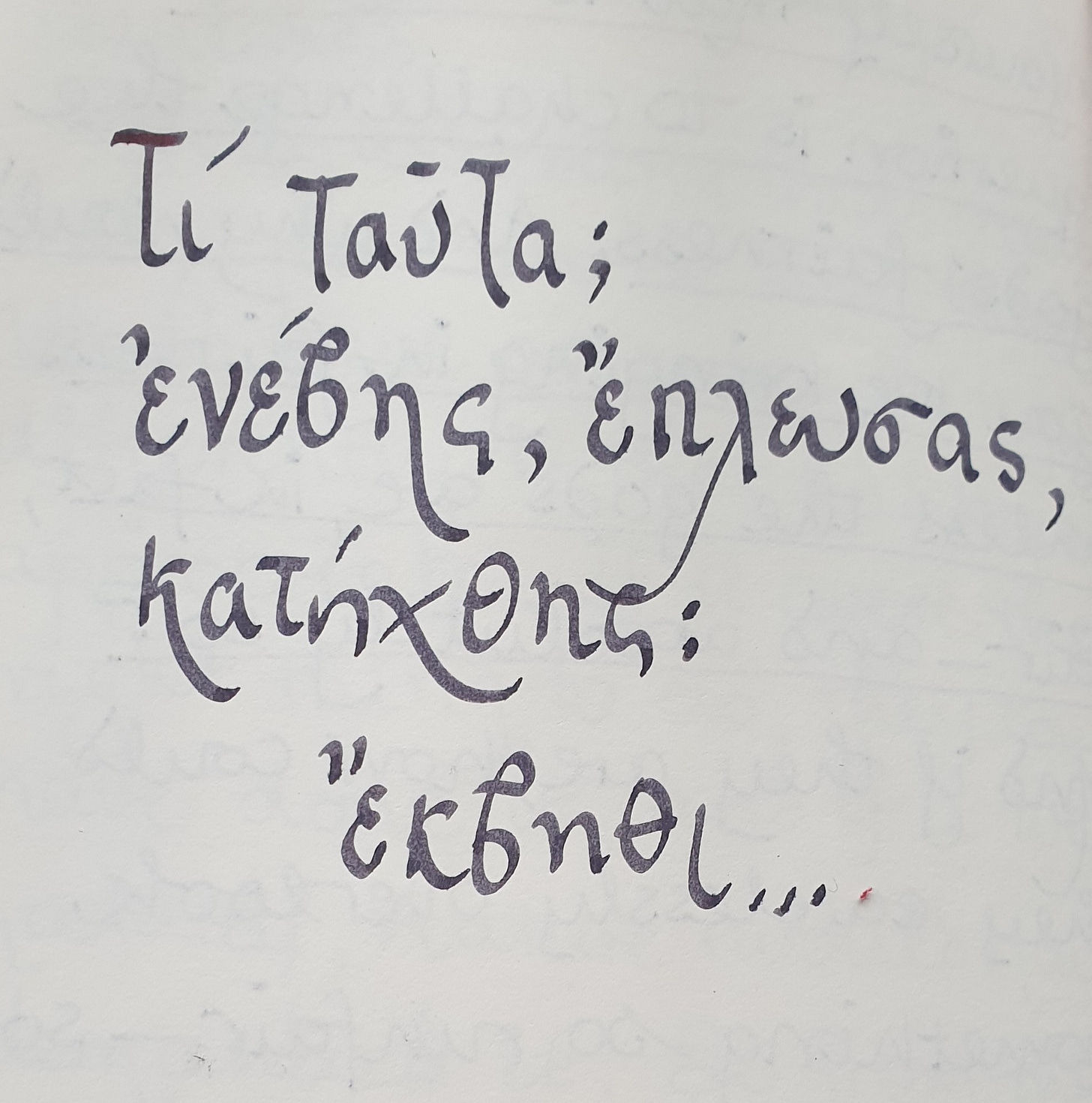

The heart meets the (left) hand in an embrace of imperfection

“What of it then? You embarked, you set sail, you made port. Go ashore now.”

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 3:3 (tr. Martin Hammond)