Letting Go...

A house clearance shows what to let go and what to hold on to

It’s the second Saturday of the month again, which came and went (for September and October) without anything from me. So here I am, three months – and a huge distance – since the last post.

Well, here’s the explanation: I was in Greece for the whole of September and the best part of October. The first ten days were a kind of holiday, but the rest were a difficult process of letting go that is not over yet.

How can it ever be over? The whole process of a life is a series of letting-go moments, some more momentous than others. But this seven-week period was a crash course in letting go, and not just my grandmother’s vintage porcelain service and my mother’s furniture. These were just the anchors for much more: I have yet to begin processing of how difficult it was to let them go because of what they meant and the tales that hang on them. But this is a path I will take in time.

It has been a difficult process, because Mama had been a hoarder all her life. She was averse to throwing things out, even giving them away. Whenever my sister Eleni or I suggested helping her to clear out, she got upset and retorted in a passive/aggressive tone, “you can throw everything out when we are dead!” And so it happened: only both Mama and Baba have been dead almost eight years now, and I have thrown things out in successive waves every time I returned to Athens. Every time I made a little progress with a lot of difficulty, never quite finishing the task. Every time I locked the flat up and returned home to Tehran or London, with a nagging sense of unfinished business.

But this time it was different: the extended UK lockdown galvanised my determination to finalise this task. Giving away the objects that Mama had kept all her life felt like a betrayal. And yet, I wanted to give things out, to let the flat breathe, open up space for the new. I took some comfort from the idea that furniture and objects that I had known all my life would become a part of someone else’s life. I saw signs that this clearance was a good thing.

A four-leaf wardrobe, part of my Mama’s trousseau brought over from Egypt, had stood in my parents’ bedroom since before I was born. It was dismantled more easily than an IKEA wardrobe (was there a sign in that?) and sold to a man for the countryside home he would retire to.

Mama’s display cabinet was her pride. It had housed objects from my father’s trips around the globe: a Chinese ivory carving of a fish; a Japanese geisha, coloured in orange and turquoise; a cloisonne sugar bowl with a snarling dragon on the lid. As soon as the ceramics collector who bought it took it home, he sent me this photo with the message “we’ve given new life to old memories.” A lot of his ceramics were turquoise, the colour of the Mediterranean and my own favourite.

The extendable dining table and six chairs, also brought over from Egypt, were sold to a couple for their adult son and daughter who’d just moved to Athens and could not afford new furniture.

The dining room sideboard had housed my grandmother’s 24-place setting antique porcelain dining service. She rarely used it, and passed it on to my mother for her trousseau. Mama only used six dinner plates as our everyday service, but again the rest (soup tureens, fish serving plate, eggcups, sauce boat and all the paraphernalia) were hardly used. Mama kept it for my trousseau, but since I married somewhat ‘unconventionally’, I never took it with me to London, nor later to Tehran. I was happy when my sister Eleni offered to take it, while the sideboard was sold to an artistic enterpreneur in Crete, who buys old furniture, refurbishes and sells it.

But the letting go process is far from over.

…and holding on to

If all this sounds like good progress, let me confess that I have packed and shipped the following to London: eight boxes of old photos, school report cards, postcards, letters, books, my favourite doll and a few mementos. They are awaiting customs clearance as we speak.

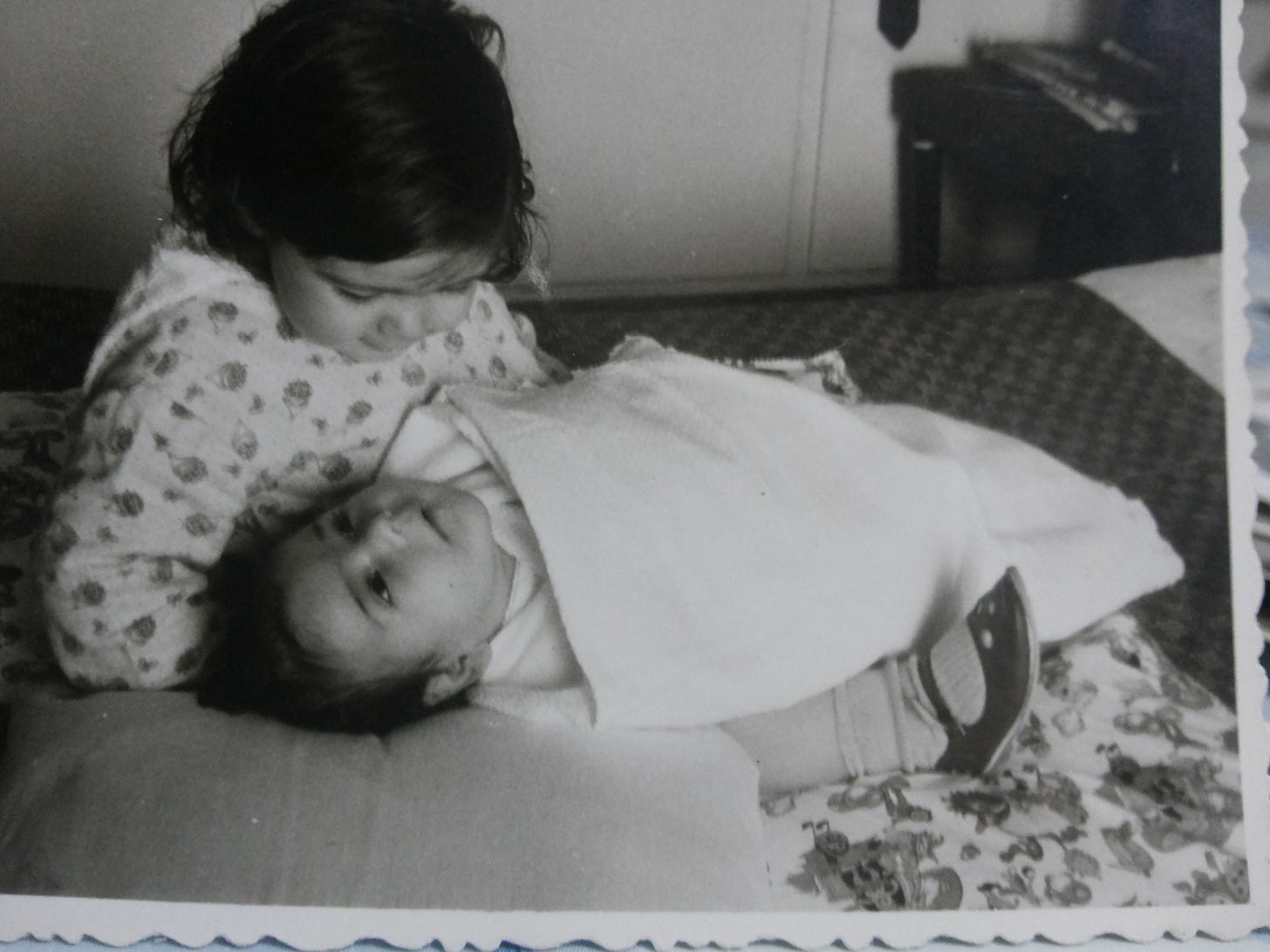

These boxes are the distillation of several lives in the Athens flat, like my first photo with my sister Eleni.

I sit on a waterproof mat (these were times before disposable nappies) on my parents’ bed, wearing a pair of red leather dolly shoes. The photo is black and white but I remember the shoes were cherry-red. Eleni, swaddled, lies across my lap. My face is bent over hers, so only the suspicion of a smile is visible, but her face is turned up towards mine, her lips half open, a bewildered expression across her face.

Eleni and I are together in many, many photos, as we were in life until early youth. Then life and distance happened, until recently when the distance closed. No matter what I let go, this bond, intangible but more real, I am holding on to.

Came across

Writing and contemplation practice

Something happened in me in the seven weeks I spent in Greece. It was the longest period I spent there in the thirty-four years since I left. I was surrounded by relics of my whole life since birth and traces of the last years of my parents’ life. I often sat on the old sitting room sofa, at the exact spot where Mama let out her last breath. She had not been happy, not even content, so I feel that the flat has absorbed the dejection, which I feel very clearly.

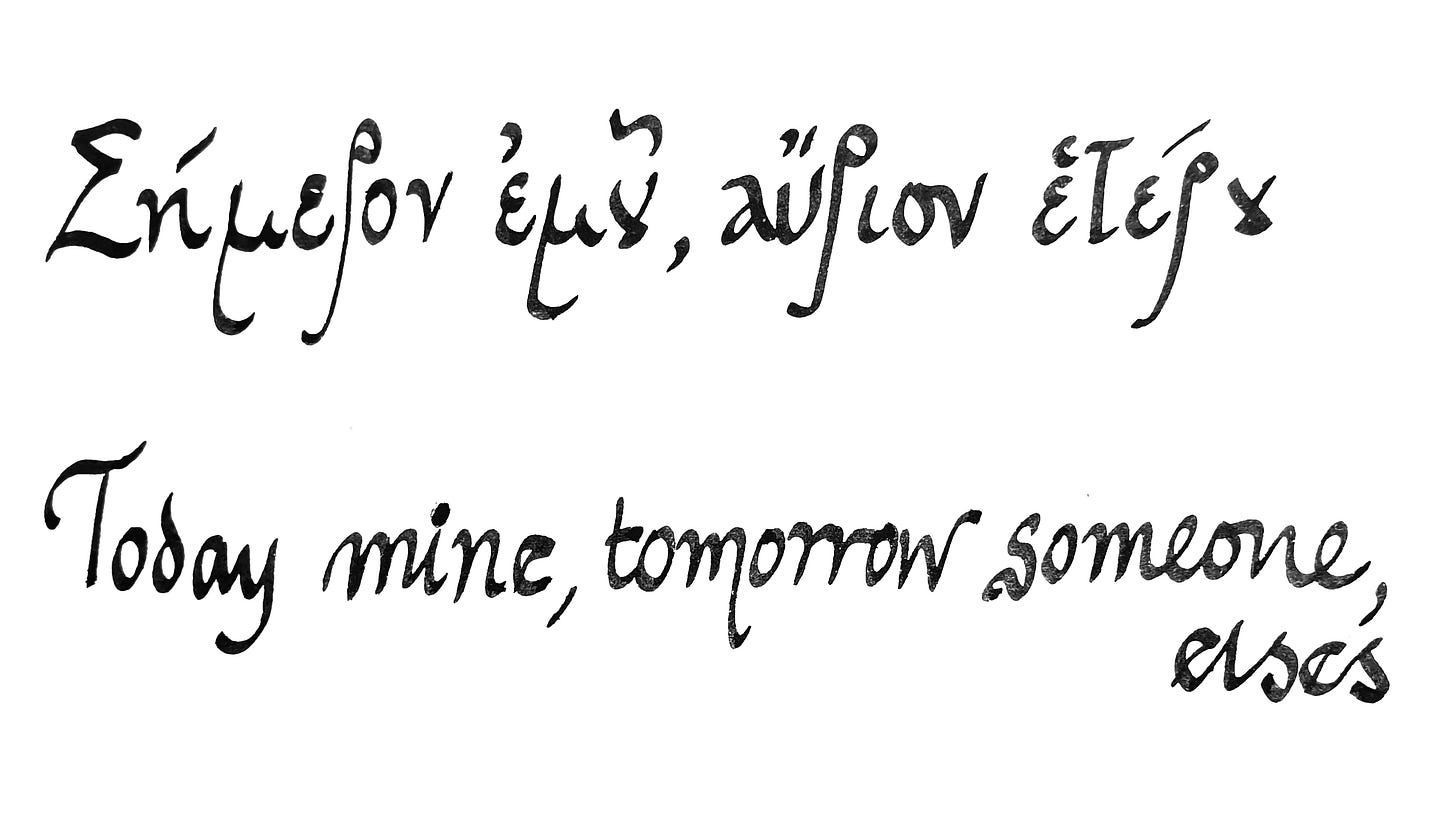

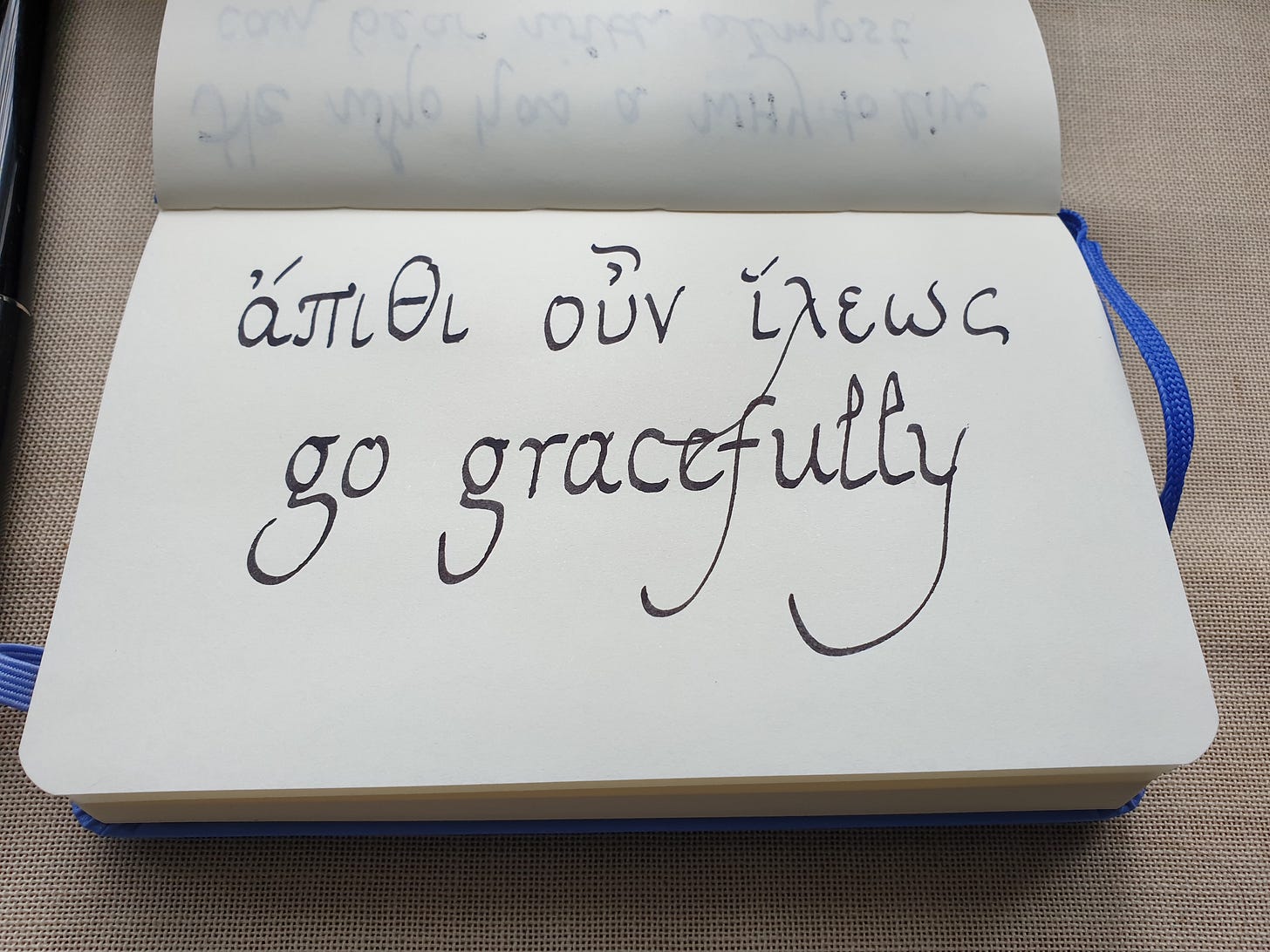

I don’t recall ever having been happier to be back in London. I had to leave Athens, but reminded myself the lesson I learned over a lifetime: that leaving never solves problems, it merely removes them from my immediate concerns. Then I came upon the 28-Day Joyful Death Writing with the Stoics with Kathryn Koromilas at The Stoic Salon. And if “joyful” and “death” sound incompatible…well, I thought so too. Almost one week in, I find the contemplation and the practice uplifting and, yes, quite joyful. A lesson from Marcus Aurelius, in my own words:

When the director of my life’s play orders me off the stage, let me go gracefully, knowing that my role is complete at that moment.

There is still time to join in!

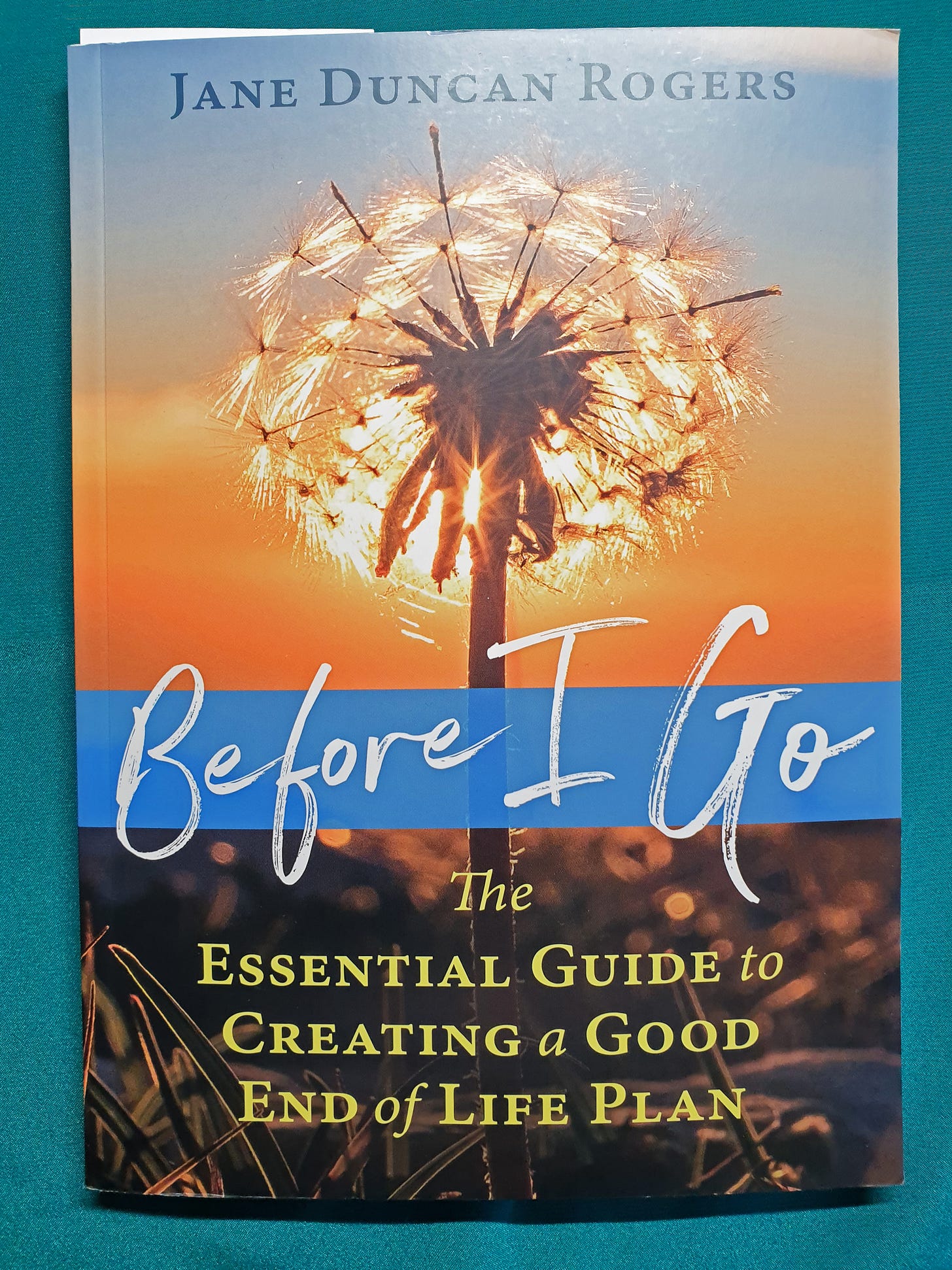

Book

Before I Go: The Essential Guide to Creating a Good End of Life Plan by Jane Duncan Rogers

The synchronicity of it all: this is the book I need to read and act upon so that after I am gone those left behind won’t have to go through what I had to after my parents’ death. I have only just dipped into it, but it seems like a gentle, down-to-earth approach to removing the fear and the worry of leaving unfinished business. Possibly the best parting gift one could ever give.

Documentary

Another piece of the puzzle: Dead Good directed by Rehana Rose (2019), a feature documentary about the ritual of caring after death. It highlights how attitudes towards care after death are going full circle, with the care returning back to the women, as it has traditionally been. I loved the idea of a person’s funeral reflecting their personality rather than following formats set by…who? By tapping into emotions shared by us all, it turns into a life-affirming experience.

Quote

If you liked this post, please share

If you like Some Little Language, do share

Would you like to read more?

Until next time!

Sending love, letting go of physical things often much harder than we think xx

Thanks for the book references. Being Mortal was a helpful book for me. http://atulgawande.com/book/being-mortal/