Letter to Baba, the sea-captain

In memoriam of a parent whose absence taught me so much

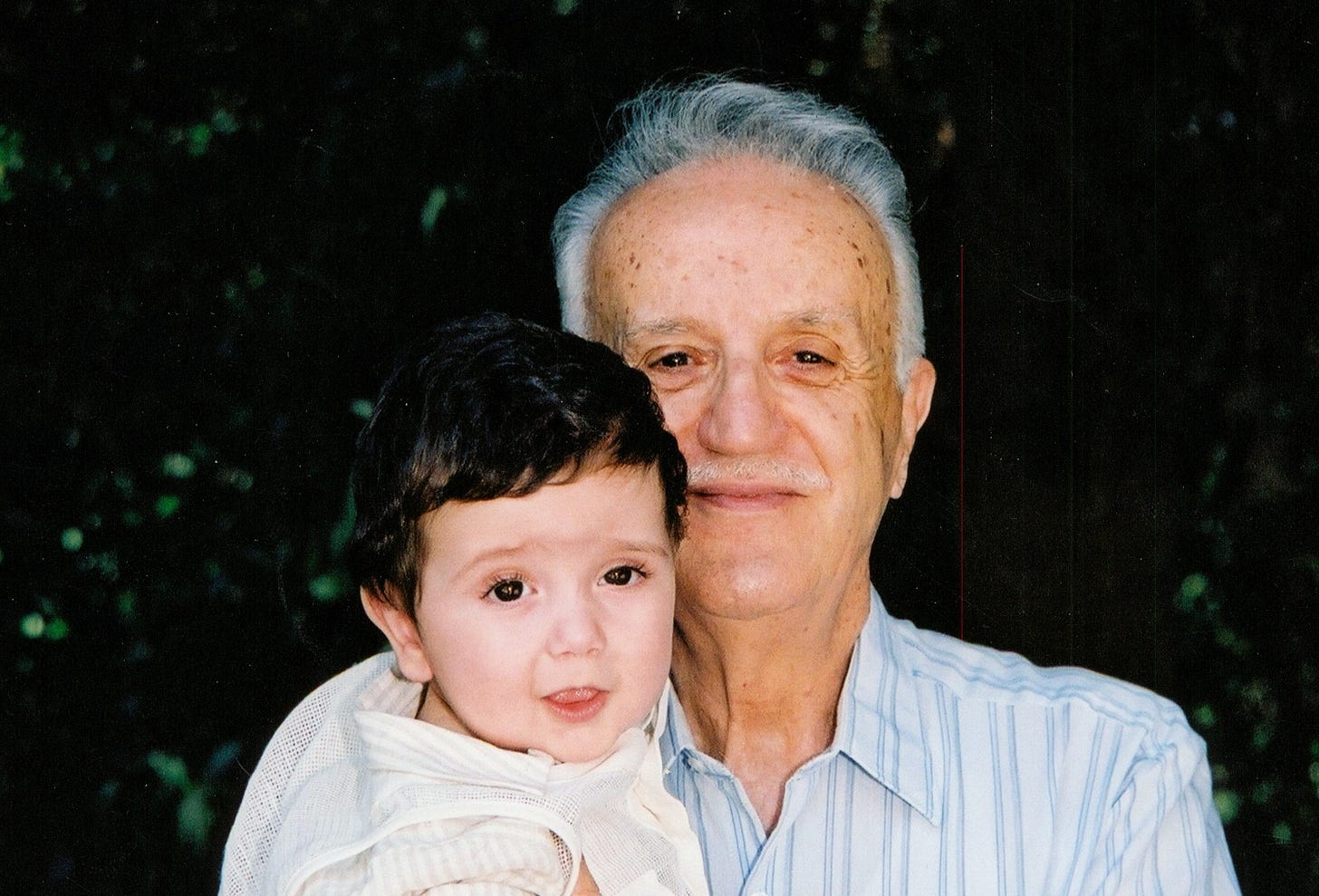

(Baba and Eleni’s baby who took on his name, Antonis, in 2001, the year he was diagnosed with dementia)

In my previous post I mentioned the letters I wrote every week in 2014, as I tried to come to terms with the loss of both parents - and much else.

Five days before my father died, I wrote this entry in my diary:

The bizarre process of dementia took Baba on a reverse journey of over a decade: from independent adulthood, he progressed to childhood, when he clapped his hands, delighted at watching movies of animals, playing games and drawing with crayons. About three years ago, he took his last steps and slipped into bed-ridden infancy. He is now past the babbling stage, only smiling when he hears a familiar voice. We can only observe him and feel helpless.

Eleven years ago exactly today, Sunday 23 February 2014, Captain Antonis sailed off too. He retired when I was sixteen, and the two of us only spent seven years full-time together until I left Athens for London at twenty-three.

This letter came out in September 2014, fully-formed, unmediated. I have made some minor edits and added photos.

***

September 2014, Shahrerey, south of Tehran

Dear Baba,

You left too, thirty-five days after Mama, maybe because you had already borne too much separation, but unlike Mama who suddenly fluttered away, your departure had been as slow and poignant as a ship's gliding away from a port for the very last time.

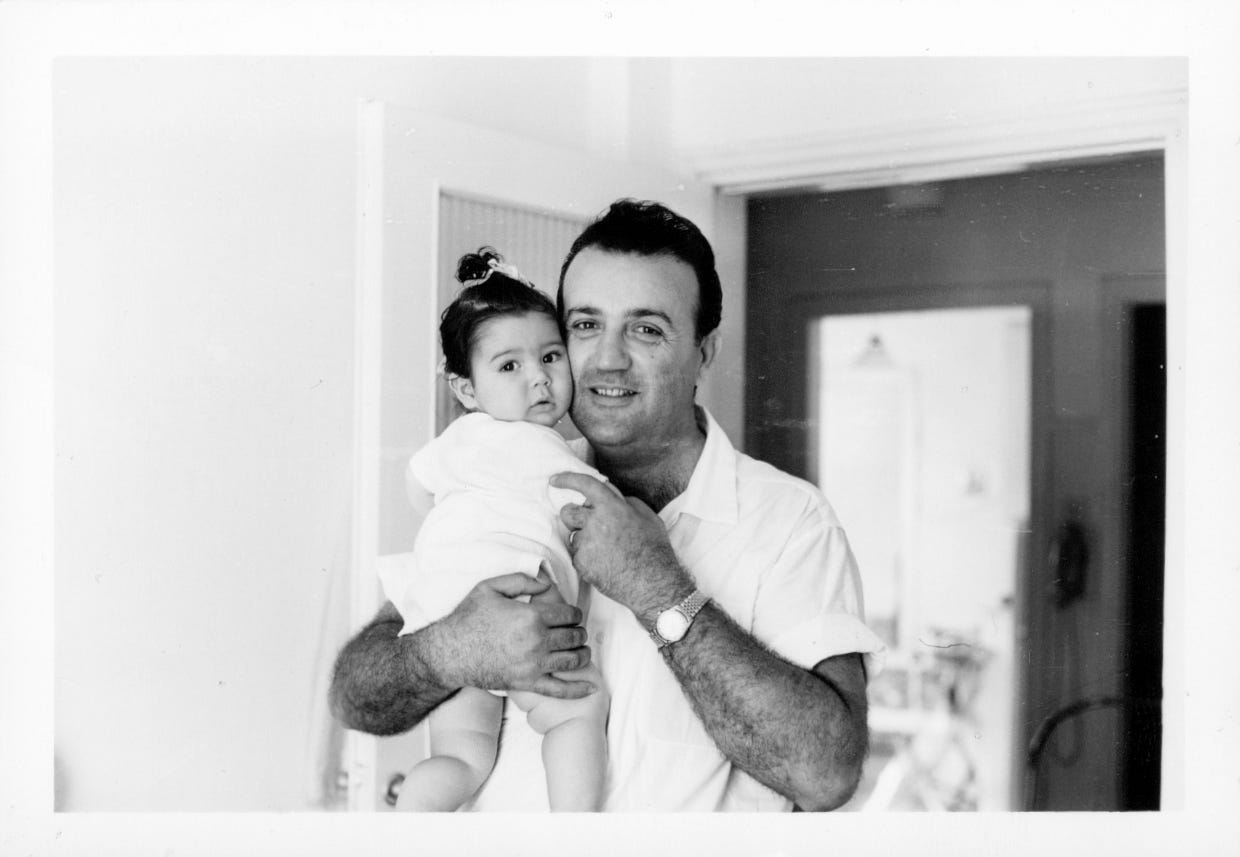

Throughout my childhood you had always been away; even the day I was born you were crossing the Atlantic, and the news of my birth reached you by telegram when the ship docked. Mama had been taken to the maternity hospital by her parents and uncle Yiannis, who was more or less your age, so everyone thought he was you. The first glimpse you had of me was a small black and white photograph of Mama holding her swaddled bundle of joy in the front balcony and inscribed Sofia, one week old. This photo lived under the glass top of Mama's make-up table until the day she died.

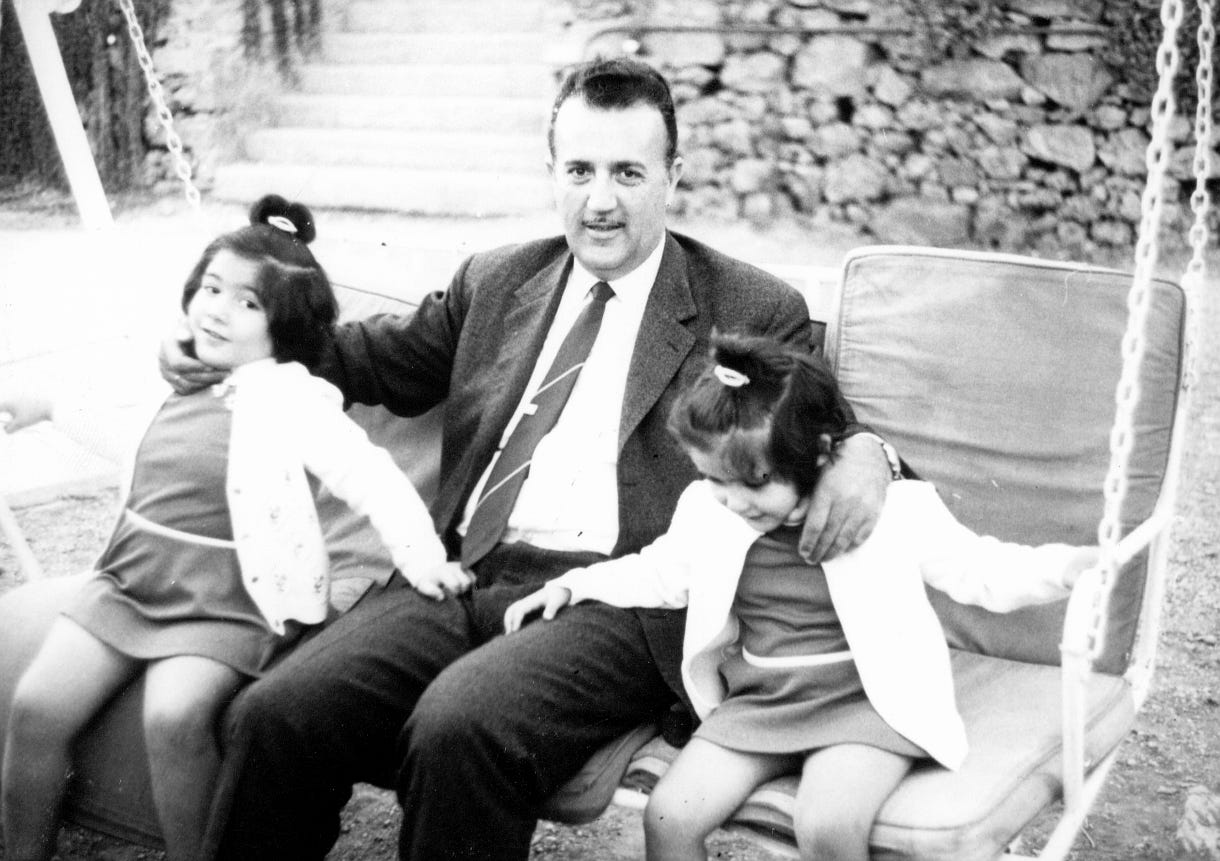

I saw you for the first time six months later, when you got three week’s leave to come to Athens for my christening in May 1965. You and mama had been trying for a baby for more than five years before I came along, so little did you think that another baby would follow so soon after me, but it did. You left a few days after my christening, and next time you came home again, you found two daughters whom you hardly knew. My sister Eleni was born fifteen months after me.

I was used to mama’s numerous uncles, cousins and brother, so when you came home next, I must have thought that you were just another relative. I did not realise you would be staying, nor that you were my father. As the afternoon wrapped into evening and then into night, and I saw you putting on your pyjamas and brushing your teeth, I began to get worried. I sidled up to Mama and asked her why you hadn’t left. She said that you were my Baba. “No!” I protested, “my Baba is there!” pointing at your silver-framed photograph on Mama’s bedside table. Whenever you told that story, you added that it had been the saddest moment of your life, my black-and-white Baba. Until then that is, because I gave you more later on. You said say this memory had hurt you ever since, so it was a good thing that after a time memories like this could not hurt you anymore.

You also said that you decided to give up smoking when I refused to sit on your lap because you smelled of cigarette smoke. Whenever you told that story, I teased you that this wasn’t true, and that you decided to give up when you realised it was bad for you. You smiled and said, “No, no, it was because of you.” I still doubted it, but I was happy in my heart because you would say it.

We hit it off soon after the photo incident, because you were loving and playful and always joking. You hugged and kissed Eleni and me all the time in the short times you were with us. Mama kept telling you off because (she said) we would turn into spoiled brats, which is probably why she avoided any bodily contact with us. You retorted that you had to make up for the times you weren’t there. Even though you were thirty-eight when I was born and well into your forties when Eleni and I were old enough to speak and play, you got down to play with us: you filled up the bathtub and put our toy sailing boats in it, blowing on to the sails to pretend that the sea was rough. Other times you put on your burgundy dressing gown, got us to take off the clothes off our dolls and pretended to be a priest christening them in a washing tub.

Once Mama said, “Your dad is getting older: just look at the wrinkles at the corners of his eyes.” I disagreed: you had wrinkles because you smiled a lot, and you continued to smile until the very end, even when you could not speak anymore. For me, you have always been the noble, handsome Captain Antonis, elegant and tall, from the moment I realised that you were not a photograph until the moment I stood at the end of your grave as your coffin was being lowered into your parents’ grave. Always the sea-captain, your last trip was a sea journey from Athens to our home island, Kasos.

You helped me get used to the idea of something always missing from my physical world, but always present and precious. First you were a black-and-white photograph, then a loving figure who never raised voice or hand; absent in the flesh, but present in so many ways.

Whenever you came home, you brought souvenirs from exotic places: Japanese dolls dressed in real fabric kimonos; Chinese carved ivory balls; Nigerian swords in sheaths made of leather and goatskin. But for me, you brought something much more valuable, the excitement for languages and cultures that has defined my adult life.

The summer of 1969, before I was even five, the opportunity came up to visit you in Naples, where the ship you were in charge of would be under repair. Eleni was left in Yaya's charge, and Mama and I flew out to Rome and then to Naples. This was my first time on an airplane, and I did not want to be strapped onto my seat because the rough navy-blue upholstery fabric tickled the back of my naked thighs. Mama reasoned, cajoled, bullied me, but it was of no use. Hearing her speaking to the air-stewardess pouting her lips and rolling her 'r's (must have been speaking in French) and the air-stewardess answering her in the same mix of incomprehensible sounds was the trick needed to immobilise me for long enough to be strapped in.

My next surprise when we got to the ship was hearing you speak in a funny way too, but different from Mama's: this was full of music, like singsong, and generous, open vowels. (Later I found out this was Italian, which you learned at high school in Rhodes.) When I got back to Athens, I pretended I could speak all those languages when I played with Eleni, and dreamed that one day I would be speaking as easily as you in Italian, English and Spanish.

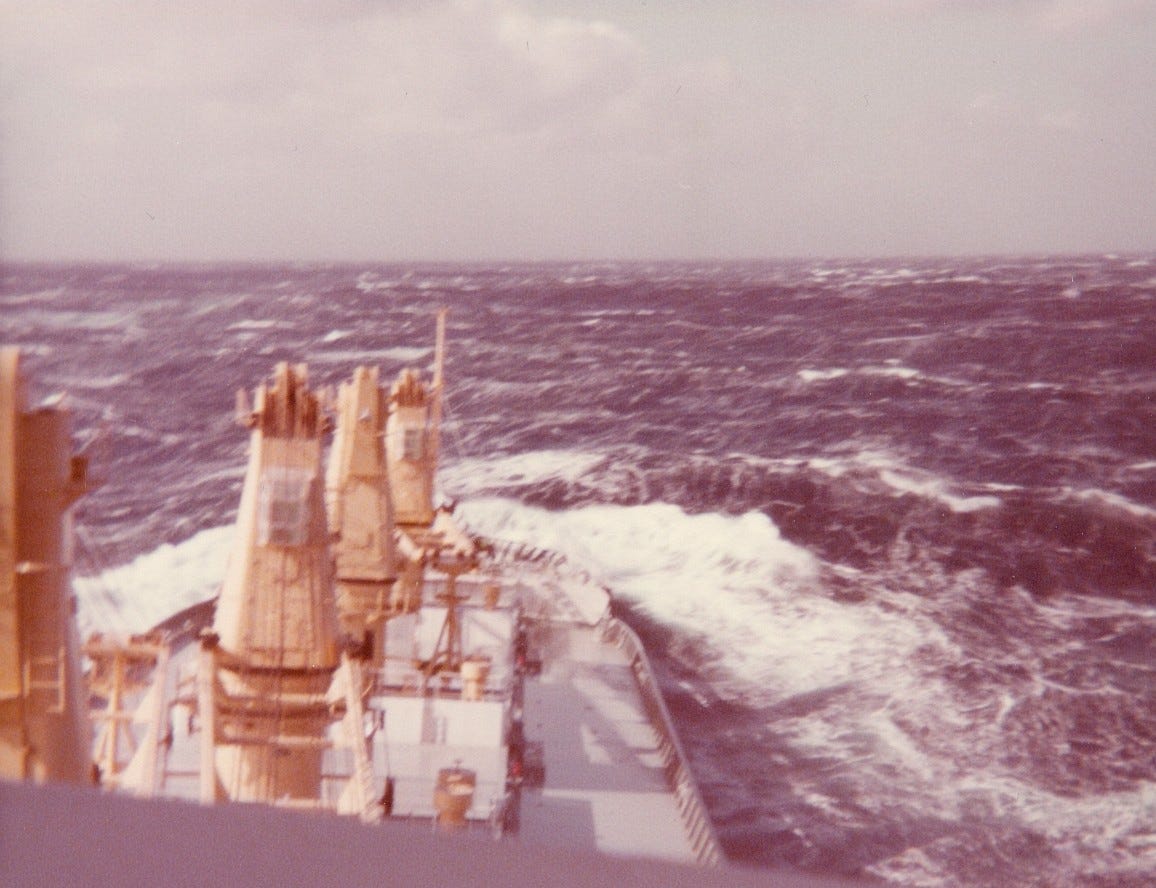

In 1974 Mama, Eleni and I joined you on board of the bulk carrier M/V Star Castor from Hamburg, Germany to Gijon, Spain, a sea journey of around 5 days, 1178 nautical miles. We sailed through the River Elbe, the North Sea, the Ijssemeer Lagoon, and the English Channel. As soon as the vessel was out in the Bay of Biscay, strong winds begun buffeting it head on. In one moment, the ship’s prow rose up as if it would take off, was suspended mid-air for a moment, and would then plunge to the depths, as a huge wave burst against it and flooded the decks (Clips like this take me back to this childhood memory.)

(Photo by Baba in 1974)

We had often travelled from Athens to Kasos, but this was nothing like the Aegean Sea: this was a full-blown Atlantic storm. Unable to stand upright, the three of us lay sideways on your double bed, as the ship’s movement rolled us once to the left…once to the right…and back again. Poor Mama, seasick and mostly silent, kept her eyes closed, from time to time complaining that Eleni and I made too much noise, whooping and giggling, as if we were on a funfair ride. After a couple of hours, you came down from the bridge to check up on us.

“Baba, isn’t this dangerous? How the waves hit the ship from the front?” I asked you.

“It can be - the ship can break in two…” You must have seen the fear in my wide-open eyes. “But we won’t let it get to that, will we? That’s what a good captain does:

Slows down as much as they can.

Adjusts route so that the waves come at the ship from the side. Even if she rolls sideways, she’ll always come upright again.

Keeps destination in mind, but doesn’t worry if the journey takes longer. It’s more important to get there safe and sound, than battered and on time.

On the whole it was hard growing up mostly without you, but you taught me that it was possible to love, even from afar, and to have a beloved image warm my heart. When I felt rejected and unloved by Mama’s unexamined words and harsh tone, I went to my room, thought of you and of how you loved me, opened a book, looked at a card you’d sent me. You showed me how to find comfort inside me, in my thoughts, in reading, in learning.

I started learning English when I was ten. You were at home when after a couple of lessons, I brought my dictation test home with “Excellent!” written over it. I didn’t even know what “excellent” meant. Even though I could see no mistakes marked in red, I thought it might mean something like “eksi” or six out of ten, so I was worried that Mama would tell me off. But you took the paper in your hand, and your face lit up, and you said it meant “arista”, that is full marks. Years later, when I got to university to study English Literature, you told me that on that day you had decided to start saving up for my study abroad. You were the only person who was proud of me; Mama said that no matter how much I study, I would eventually end up at the kitchen sink.

Now and then, you sent me a letter; strictly speaking it was not a letter, more an envelope containing a brief note and a ten or a twenty dollar bill wrapped in carbon paper. For some time when I was very small, I liked individually wrapped moist tissues, and you sent me one of those in each envelope. They had Japanese characters printed in turquoise all over the wrapping. In a little free space in the corner, you squeezed, “To my Sofia, with kisses, from Baba.” I hoarded those in an old handbag of my mother’s, thinking that they would keep for ever, which they didn’t, and finally dried out, like everything else.

I can’t remember a New Year’s Day when you were home. Mama used to cut up the Vasilopitta, the New Year Cake, naming the pieces one by one and turning each one upside down to see whether this was the one to get the lucky coin. Next time you rang to wish us happy new year, she remembered to tell you whose was the lucky coin.

I only remember the New Year’s Day after my thirteenth birthday. We did the countdown together, and spent New Year’s day together. Santa Claus (who comes to Greece on New Year’s Day, not Christmas) had brought me a set of two colour-by-number paintings of cargo ships. You were scheduled to fly to your next commission on 2 January. The atmosphere was heavy in the sitting room, with Mama withdrawn into one of her moody silences, so I sat at my desk in the room I shared with Eleni, opened the oil pots and began to paint.

Before lunchtime your taxi rang the bell. You came to my room to say goodbye. I can’t remember your hug or your kiss; I only remember continuing to paint in the colours of the ship that got smudged because I couldn’t see clearly.

Your life was a series of goodbyes, with the last, drawn-out one the most painful of all.

How many of these memories were washed away as your brain shrank?

Have they disappeared, or are they still there because I cherish them? Are you still there, somewhere?

I still love you (not “loved you”, because I am still alive, and I still do the loving) for everything you taught me, but mostly because your love was deep and inexhaustible, even when I broke your heart.

Your Sofia

Thank you, Suchandrika 💙💙

As long as there are such loving memories your dear father (and my beloved nonos) will never by forgotten. I have him on my memories as a strong and gentle, handsome and kind, openhearted and generous but most of all I had him very close to my heart. Excellent (and not exi..) writing as always Sofia, thanks you for sharing these nice photos as well!!